This isn't a novel. It is interviews with First Nations youth that Deborah Ellis had met over the course of two years. Each chapter is a different story. Stories are told in first person. After a while, I figured I got the gist of the book, but something told me I should continue on. After reading story after story after story, there is a great impact on the reader's heart. There are so many amends to be made for all the First Nations people have gone through. I think they will rise up though. I feel like times are changing for their entire culture. Perhaps that is why it is called Looks Like Daylight. The last page is a story about Waakekom, an Ojibwe boy who is 16 from Saugeen First Nation in Ontario. He says:

“My spirit name (“Waasekom”) means ‘when it’s night and lightning fills the sky and it suddenly looks like daylight,’”.

Like she has in the past, all the royalties from this book go to the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada (www.fnccaringsociety.com)

Some parts that really struck me:

p. 117 The US government referred to the Cochtaw Nation as one of the Five Civilized Tribes, along with the Cherokee, Creek, Chicksaw and Seminole. They were called civilized because many had begun to adopt European ways - living in log cabins, wearing European style clothing and attending school. But in 1829, President Andrew Jackson decided that assimilation wasn't good enough. He launched a plan to remove all Native Americans from the US South to places west of the Mississippi River. The idea was to move 60,000 Native Americans who had been living in the Eastern Woodlands since time immemorial and put them in an area vastly unsuited to their traditional way of life. The bulk of the Five Tribes were rounded up at gunpoint and then forced to walk, leaving behind farms and homes. One in four died along the way.

p. 151 Lacrosse originated with the people of the Ongwahonwe Haudenosaunee, or Six Nations, the people of the Longhouse....also known as The Ancient Game/the Creator's Game, its purpose was- and still is-spiritual. It's offered up to the Creator asa prayer for healing or as an expression of gratitude. Some people are given miniature lacross sticks when they are born, & when they pass, a lacrosse stick is placed beside them.

*Lacrosse = Canada's National Sport

p. 175American Indians have a higher percentage of enrollment in the armed services than any other group. The first Native American recipient of the Medal of Honor (1869) was Co-Rux-Te-Chod-ish, or Co-Tux-Kah-Waddle, who served with the Indian Scouts. In WWI, a law was passed requiring all Native American men to register for the draft even though they were not considered citizens and could not vote .Many thousands voluntarily joined the military. Many others protested this law. In Utah, for instance, the protests were so vehement that the army was called in to stop them.More than 44,000 Native Americans served in WWII, where Navajo Code Talkers played a pivotal role. Ten thousand served in Korea and 42,000 in Vietnam. Ten thousand of those who have served have been women. 18,000 have been sent to Iraq or Afghanistan. First Nations people in Canada have also served with great distinction.In Canada, Aboriginal veterans were for a long time not entitled to the same benefits granted to soldiers of European descent. Native veterans were told that since they were not considered Canadian citizens (First Nations people did not obtain the right to vote until 1960), they were not eligible for veterans' benefits. And it wasn't until 1992 that Aboriginal vets were allowed to lay a wreath at the National War Memorial in Ottawa on Remembrance Day.At powwows, veterans are treated with special respect, and a ceremonial dance is done in their honor.

Goodreads says:

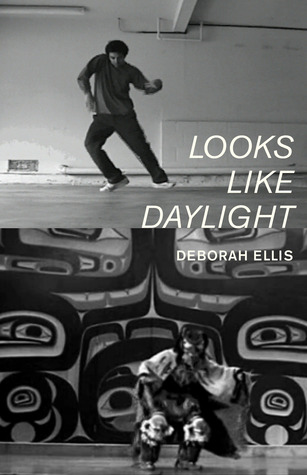

After her critically acclaimed books of interviews with Afghan, Iraqi, Israeli and Palestinian children, Deborah Ellis turns her attention closer to home. For two years she traveled across the United States and Canada interviewing Native children. The result is a compelling collection of interviews with children aged nine to eighteen. They come from all over the continent, from Iqaluit to Texas, Haida Gwaai to North Carolina, and their stories run the gamut — some heartbreaking; many others full of pride and hope.

You’ll meet Tingo, who has spent most of his young life living in foster homes and motels, and is now thriving after becoming involved with a Native Friendship Center; Myleka and Tulane, young artists in Utah; Eagleson, who started drinking at age twelve but now continues his family tradition working as a carver in Seattle; Nena, whose Seminole ancestors remained behind in Florida during the Indian Removals, and who is heading to New Mexico as winner of her local science fair; Isabella, who defines herself more as Native than American; Destiny, with a family history of alcoholism and suicide, who is now a writer and powwow dancer.

Many of these children are living with the legacy of the residential schools; many have lived through the cycle of foster care. Many others have found something in their roots that sustains them, have found their place in the arts, the sciences, athletics. Like all kids, they want to find something that engages them; something they love.

Deborah briefly introduces each child and then steps back, letting the kids speak directly to the reader, talking about their daily lives, about the things that interest them, and about how being Native has affected who they are and how they see the world.

As one reviewer has pointed out, Deborah Ellis gives children a voice that they may not otherwise have the opportunity to express so readily in the mainstream media. The voices in this book are as frank and varied as the children themselves.

No comments:

Post a Comment